Iron Clipper [12M] – (Excellent detail in Dive Dorset: 74 p 71 & Clarke:) GPS; 50 34.65N; 02 28.50W. (LARN, 1872) – Chesil Beach, Ferrybridge. Featured in Portland Museum, Wreck No. 4. See also the Times Reports

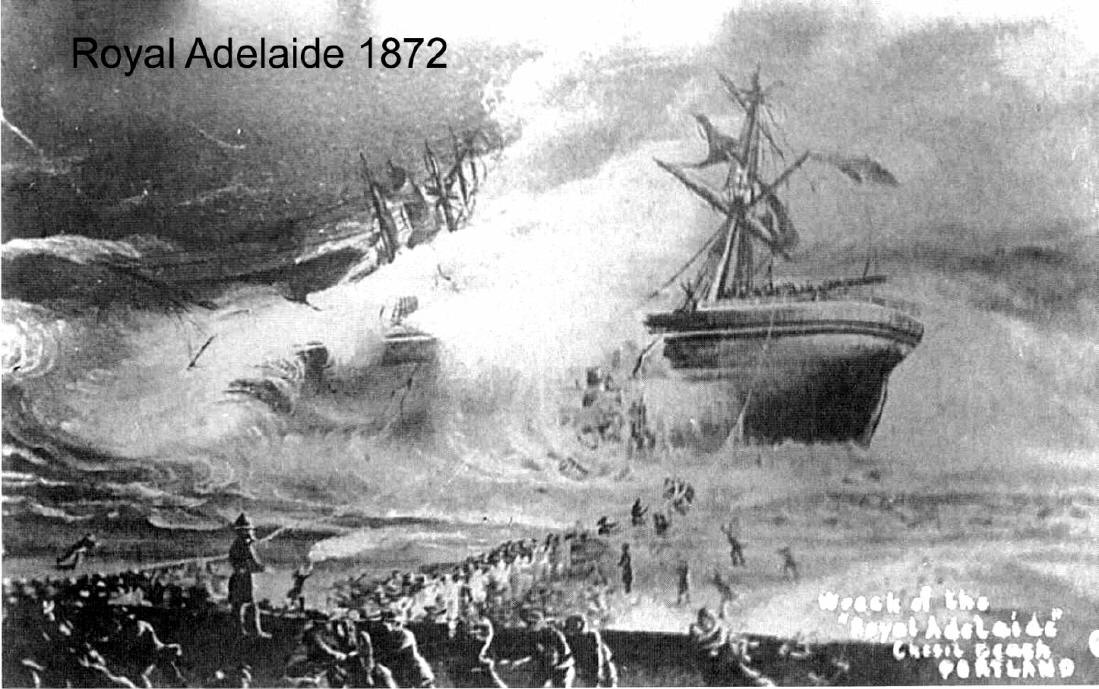

Source: Illustrated London News, 7th December, 1872.

“The loss of the Royal Adelaide, bound from London to Sydney, which vessel was wrecked on the western side of Chesil Bank, the narrow isthmus of Portland, on the evening of Monday week, has been mentioned as the most grievous disaster caused by the late gales. The persons drowned were Mr. Powell, the chief mate, Mrs. Fowler, Rhoda Bennion, and Catherine Irons, female passengers, Edwin Ruddock, and John Edwards. A gentleman from Weymouth, Mr. Hamilton Williams, who saw the ship go ashore, has sent us a sketch, with the following description of this terrible scene:-

“With two companions I set out by the five p.m. train from Weymouth for the Chesil Beach, hearing that a large ship-rigged vessel had been seen all the afternoon in the bay with apparently small chance of escape. Arriving at Portland, we ascended the Chesil Beach, and found the coastguard in full force, burning blue lights to attract the notice of the ill-fated ship. Far to leeward we could occasionally discern a glimmering light, and we set off in its direction along the beach as fast as we could run. Presently a blue light flashed up from the vessel, whose outline we could just see, blurred and dim, through the driving scud. Almost as we came opposite her she drifted broadside on to the beach, despite of her anchors, which found no holding-ground. Fearfully she heaved and rolled in the awful sea. It seemed as if the delivering rocket was never going off on its message of help; but at last, straight as an arrow, away it sped right through the rigging of the helpless vessel, which we made out to be a large ship-rigged craft of apparently 1500 tons. The cradle was rigged, and the coastguard worked like more than men. The passengers and crew were hauled ashore. Through the boiling sea came one after another, grasped long ere they reached the shore by the friendly arm of some stout seaman. Then we began to learn that they had women and children on board, and the fear that the ship might break up before all were saved grew more intense. The first mate had already been drowned, madly trying to jump, unaided, from the ship. A woman too was drowned, falling overboard. The men lighted a tar-barrel and put it so as to throw as much light as possible upon the scene of work; and many blue lights were kept burning, giving even a better light than the barrel. Soon, with an awful lurch to seaward, the mainmast went by the board, the mizzen topmast having already gone. In a few minutes it was seen that the ship had split right in two, a little abaft the mainmast… Once commenced, the work of destruction was not long, though still the cradle was going to and fro, and still there remained others to be saved. These were all congregated astern; and when the last two or three were already in the cradle, about to try their fate, as many others had happily and successfully done before them, the rope broke, they fell into the cruel surf, and were seen no more. The ship now began to disgorge through her riven side the cargo she contained; and bales, boxes, crates, and casks drifted ashore in quick succession. Then we left the shore, seeing the ship a hopeless mass of shattered wood; and I do not think that any one of us there will ever forget the impression made on us by the wreck of the Royal Adelaide.”

An official inquiry, ordered by the Board of Trade, has been commenced at Weymouth.”

More Detail

The iron sailing/clipper ship ‘Royal Adelaide’ was Australia-bound when she left London on 14 November 1872. Eleven days later she lay wrecked off Chesil Beach, her master having misjudged his course in heavy weather as he attempted to seek the shelter of Portland Roads, for which mistake his certificate was later suspended for twelve months.

Carrying almost seventy crew and passengers and a mixed cargo (which included a large number of cases of spirits) the ship was seen to be embayed in the West Bay and driving towards the shore. Those on the beach were powerless to assist until the Royal Adelaide struck and they were able to get a line on board. A cradle was rigged up and the rescue began. It was a dramatic night-time scene, the Chesil Beach close to Portland illuminated by tar barrels and blue lights while a crowd hundreds strong looked on. Shipwreck news spreads fast and spectators arrived via the trains of the Weymouth and Portland Railway. All went well until one elderly passenger could not be persuaded to trust herself to the fragile line linking ship and shore. The ship began to break up; the line was lost and the last few on board were swept sway and drowned.

If the rescue had enthralled the watching crowd, the cargo thrown up by the dying ship was to excite them even more and wholesale looting began. The cargo contained a fine array of goods which were soon spread out along the shingle – everything from hats and gloves and boots to herrings, hams, tea, coffee and figs. Despite the efforts of the coastguards, police and military much of the cargo disappeared into local homes – and gardens, where stolen goods were buried to escape the searching eyes of the law enforcement officers who called in the days following the wreck. Roll call in local schools showed many absences as children joined their treasure-hunting parents at the scene.

Sadly, the tubs of spirits were to add to the death toll of the ‘Royal Adelaide’. Many helped themselves liberally to the brandy and gin casks as they were washed ashore and fell asleep drunk on the cold Chesil pebbles. Friends and neighbours were too busy gathering up cargo to take much notice but by the following morning four locals, one a lad only fifteen years old, had been found dead, killed by a combination of drunkenness and exposure. The bones of the ‘Royal Adelaide’ still lie close to Chesil beach, a ship destined for the other side of the world which got no further than the Dorset coast.

The Royal Adelaide

The Royal Adelaide was an iron built clipper. She was an emigrant ship and set sail from London on the 14th November 1872 for Australia carrying 67 crew and emigrant passengers – women, men and children. She also had a large cargo including cases of rum and spirits. On the 25th November people on the shore at Chesil Beach noticed she was in trouble and later on that evening she struck the beach broadside on. The Captain had misjudged his course. Hundreds of people came down to the beach and some even travelled by train from Weymouth when they heard. Tar barrel lights were set up. The cargo that was swept up on the shore also caused a great deal of excitement. A man from Portland wrote: “bales of beautiful cloth and silk, And boxes of gloves, made of kid, white as milk, And boots without number, of all sorts and sizes! And hats by the thousand, of all shapes and prices…”

Candles, cotton, coffee, sugar, livestock (one pig survived), brandy, rum and gin were washed up on the beach. Some of the goods were buried in peoples gardens until the coast guard had left the scene. This huge and varied supply of goods was destined to be sold to the new colonists in Australia. There was also, of course, the passengers luggage.

A lifeline with a cradle attached was used to ferry people ashore. Only one person at a time could be rescued and the women’s’ dresses made it awkward for them to climb into the cradle. Sixty men, women and children were rescued before the lifeline snapped. Seven people left on the wreck were washed away during the night and by morning the ship had sunk.

A lifeline with a cradle attached was used to ferry people ashore. Only one person at a time could be rescued and the women’s’ dresses made it awkward for them to climb into the cradle. Sixty men, women and children were rescued before the lifeline snapped. Seven people left on the wreck were washed away during the night and by morning the ship had sunk.

From: A Southwell Maid’s Diary By: Elizabeth W. Otter. Published: July, 1930.

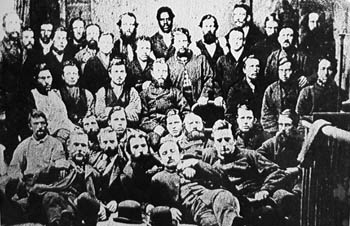

Black & White photograph. The male passengers and crew who survived the shipwreck. Many were later to record their gratitude to the people of Weymouth who took them in and gave them shelter.

Black & White photograph. The male passengers and crew who survived the shipwreck. Many were later to record their gratitude to the people of Weymouth who took them in and gave them shelter.

Bone (?) handle and metal prongs. Many knives and forks were washed up on the beach and may have been part of the cargo destined to be sold to the colonists in Australia.

Bone (?) handle and metal prongs. Many knives and forks were washed up on the beach and may have been part of the cargo destined to be sold to the colonists in Australia.

Leather soles and uppers. 12cms long x 4cms wide. Gilded buckles with black ribbon bows. Decorative stitching on tongue. One of three pairs of shoes all of the same size and all showing signs of wear. Perhaps they were part of a child’s luggage.

Leather soles and uppers. 12cms long x 4cms wide. Gilded buckles with black ribbon bows. Decorative stitching on tongue. One of three pairs of shoes all of the same size and all showing signs of wear. Perhaps they were part of a child’s luggage.

Red leather boots. 12.5cms long x 4cms wide. Elasticated sides. One of three pairs of shoes all of the same size and all showing signs of wear. Perhaps they were part of a child’s luggage.

Red leather boots. 12.5cms long x 4cms wide. Elasticated sides. One of three pairs of shoes all of the same size and all showing signs of wear. Perhaps they were part of a child’s luggage.

All these can be seen at the Portland Museum.

All these can be seen at the Portland Museum.

The Wreck Of The “Royal Adelaide.”The 25th of November, Eighteen Hundred and Seventy-two She drove in just after ’twas dark A clipper built ship, and the people all say Then by a line, the first mate tried to cross Now when the sixty were safe on the shore But barrels of rum, brandy and gin There were boxes of candles and sweet-scented soap

|

While ducks and geese formed part of the losses And gentlemen’s dogs and two fine horses. Yes, those things with rope and broken timber Formed a sight and a scene many long will remember. People from Portland, from Wyke, and from Town Which formed a crowd of hundreds, yes, more Than thousands at one time stood on the shore.All anxious to save their own brother man, All willing to lend a good helping hand, High praise be to those who wet every thread In saving the lives from the “Royal Adelaide.” Now when all of the lives were safe on the shore, The majority returned to their homes once more; But many instead of going honestly back Were tempted to steal a part of the wreck. So they took something, and Ned, Tom and Harry But while some were plundering and carrying things home, In the wind and the rain to lay all the night For several were found quite dead on the beach For they loved him much and made it a rule Robert Otter.

|

From: The Island & Royal Manor of Portland Historic Sources

From the Parish Register; 424- Louisa FOWLER, drowned Royal Adelaide, 29 Nov, 1872, 72, James CROFTON curate. Stranger’s Cemetery Map ref 169

Here lies the body

of

LOUISA FOWLER

widow of the late VILLIERS BUSSY FOWLER ESO of Carne Fowler C. Mayo

and daughter of the late Major BINGHAM of Bingham Castle C. Mayo

drowned in the fearful wreck of the ROYAL ADELAIDE on the Chesil Beach

November 25th 1872

For if we believe that Jesus died and rose again even so them also which sleep

In Jesus will God bring with him

From the Parish Register;

968 – Johann Carl Frederic MAGDEBINSKY, found drowned at Folly Pier, 3 Dec, 1872, 49, Arthur HILL & H. A. TAYLOR clergymen.

Register Marginal note: (Entry No 968): Drowned in the wreck of the Royal Adelaide Nov 25, 1872 on the Chesil Beach when saving the life of others.

Also

419 – Found Drowned Name Unknown, 27 November, 1872 – Henry Jenour, Vicar

420 – Found Drowned Name Unknown, 28 November, 1872 – Henry Jenour, Vicar

Other References:

1 – Shipwrecks by Maureen Attwooll, pages 45 to 48.

2 – Archives of Portland Museum.

A Series of Times Reports

The Times: – 2 December, 1872 – The Storms of Last Week

“The storms of the last week have been attended by scenes around our coasts which surpassed even the wildness of the elements. When people in towns or villages exchange trite condolences on the weather, few of them, probably, reflect that what is mere discomfort to them is mortal agony to number of their countrymen, who on shipboard are struggling against a furious sea, or are being swept to destruction on some lee shore. But there are few hours more tragic then those in which a heavy gale is blowing. At such moments we may be only too sure that scores of strong seamen are wrestling with a cruel fate, and that helpless women and children are sinking in despair into one of the most terrible of deaths. Mining accident are sufficiently grievous, and a man with a heart must often feel a qualm at the thought of the price at which his commonest comforts are bought. But, as a rule, such accidents are mercifully sudden, and the very hopelessness of escape after the first moment of danger may in some measure deaden their pangs. There seems something more agonizing in the prolonged struggle of a fine ship, manned by strong men, with a raging element. The very effort, it may be hoped, partly numbs apprehension; but it is a fearful strain on heart and hand to be battling for hours with Nature in one of her most terrific forms, and then, perhaps, amidst a furious sea to be hanging for a few intense moments on the weakness of some slight rope. Hope, and with it terror, are never quite exhausted, and the struggle is never over, until the last merciless grasp of the wave snatches the strong life into destruction.

It is sufficiently sobering to picture all this to the imagination. But what must it be to see it? What, would it be supposed, is the kind of effect likely to be produces by witnessing year after year the wrecks of fine ships, and beholding, almost within arm’s reach, the death struggles of brave men? It may be believed that, on the whole, the severity of a seafaring life develops in our people many of the more manly virtues. But that there are frightful exceptions the narratives we have recently published of shipwrecks at Portland and at Waterford have painfully shown. The story especially of the loss of the Royal Adelaide combines most of the elements of distress we have been recalling. She was a fine ship, caught by the gale in the vicinity of Portland Bill. She was skilfully handled, and struggled with her fate for hours. The spectators onshore could observe how once and gain she bore up in vain hope of gaining the protection of the Breakwater. At length, when she was so near the shore that, in spite of the mist of the storm and the darkness of evening, her masts and sails could be seen through the gloom, she ran direct for the beach and grounded within thirty years of the land. She was so near that before a rocket could be fired some fishermen, whose bravery deserves all honour, rushed into the surf, and succeeded in throwing a line to her. Then, while the ship was breaking up with every blow of the waves, men, women and children – the captain, strange to say, being among the first to come ashore- began to traverse that perilous gulf of thirty yards. Some attempted to escape by themselves, and perished; some were swept away in the passage along the rope; and at length the rope itself broke, and the piteous sight remained of one aged woman who had refused to trust herself to the cradle in time, and who could only be left to her fate. Some ten or fourteen persons were drowned, and the rest had escaped out of the very jaws of death. Then followed the horrible scene to which we have referred. The ship at one broke up and her cargo was washed ashore apt to produce extreme results in one direction or another. They make men either very reckless or very grave; and all the most perilous employments are found to give birth to these contrary types of character. An ungovernable fit of animalism is apt to seize on minds which have been over strained by terrible scenes. The very confusion of the elements seems to enter into the soul, and body and mid are convulsed like the ship on the shore. Everything is a wreck within and without, and, to quite an old but ever true saying, men drink, for tomorrow they die. Such scenes as we have described are, happily, rare in our days; but their possibility is never to be forgotten, and the coarse passions they reveal are among the most terrible realities we have to encounter.

The Times: – 2 December, 1872 – The Loss of the Royal Adelaide

“Sir,

The account of the loss of the Royal Adelaide on Chesil Beach, near this place, a few days ago, will doubtless, have excited much sympathy among your readers for the survivors. The crew and those of the passengers who required aid were promptly relieved by Mr DAMON, the local secretary of that invaluable institution The Shipwrecked mariner and Fisherman’s Society, and sent to their friends. The local resources will, I trust, be sufficient for the relief of a few other cases of steerage passengers who appear to be friendless. There is, however, one case I venture an appeal to the public to assist. It is that of a lady and her seven children (ages from 7 to 19) who were rescued from the wreck. They had sold off everything to pay for their outfit, which is, of course, lost, and still worse, her mother was one of those who perished, and with her an annuity on which the family mainly depended for support till the lady’s husband, who is a clerk in an office in Australia, could be joined, and whose salary is very small. As this family are of high birth, and have been in better circumstances, I would prefer not mentioning the name, but am ready to give any further information privately to any one inclined to assist in placing them in the same position they were in before this unfortunate event occurred. As the Senior Naval Officer participating in the rescue, I can assure you the horrors of the scene are but faintly described in the (in other respects) truthful account given in your paper, and looking back on it now, it is marvellous to me that so many were rescued on such a night. Under God’s mercy, it can only be attributed to the skill and bravery displayed by the Coastguard and fishermen of the vicinity, who must have been nobly aided by the exertions of some on board the ill fated ship.

Captain Hare, Her majesty’s Ship BOSCAWEN, Portland and the Rev C. H. HARBORD, her majesty’s Ship ACHILLES, of Portland, will be as will as myself to give information or to receive subscriptions.

I am, Sir your obedient servant

- V. HAMILTON Captain R.N.

HMS ACHILLES

Portland November 29th

Letter: To the Editor of the Times.

Sir,

The dangerous nature of West Bay renders it, I think, a subject of some important consideration whether there ought not to be a place of refuge at the head of the bay, to which vessels in distress could direct their course. A more dangerous place for a vessel to get into in a gale can scarcely be found along the south coast, the Chesil Beach being too well known to render an comment necessary; and yet there is really no haven in the bay. Once let a ship get on the wrong side of Portland Bill, and there is no hope for it. Take the case of the Royal Adelaide. The vessel was seen within a short distance from this port, and, I believe I am correct in stating, might have made it had there been a harbour large enough to receive her. During a heavy gale from the south west a vessel cannot get into Torbay, so that, from the recent painful experience, a refuge at the head of the bay seems imperatively needed. No very extensive addition to this present harbour would, as I have been informed, render it a perfectly secure harbour of refuge, the sum lost by the destruction of one such ship as the Royal Adelaide being a great deal more than sufficient for the purpose.

I am, Sir, yours etc.

D S SKINNER, Mayor of Lyme

Lyme Regis November 29th

The Times: December 3, 1872 – A Letter.

“Sir

Being today at Green’s Sailor’s Home, a coloured seaman was pointed out to me as one who formed part of the crew of the Royal Adelaide, lately wrecked off Portland. I learnt from him that nothing could exceed Captain MARTEN’S care and attention to the ship up to the time she struck – that he scarcely ever left the deck for many days. As some remarks have been made as to Captain Marten leaving the ship, so early, the reason given was that he could not induce any one to make the venture after the first two had run such a risk in the basket, and, as an example to beget confidence, he got into the basket and with his charge safely reached the shore. It appears, too, that both anchors had been let go, and that she was not run ashore, but came on shore from the violence of the gale. The insertion of these few statements may be some comfort to a gallant seaman.

I remain, Sir your obedient servant

W HUGH PHIPPS Commander RN and Superintendent”

Times: Thursday, December 5, 1872, Issue 27552 – The Loss of the Royal Adelaide

“On Tuesday an official inquiry instituted by the Board of Trade was commenced at the Guildhall, Weymouth, before Captain WILSON, of Lloyd’s Salvage Association, and Mr STRONG, of the Board of Trade, to investigate thje circumstances connected with the wreck of the Royal Adelaide, which went ashore on Chesil Beach, between Weymouth and Portland, on the night of the 25th November, to inquire into the loss of life, and to see whether the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act had been complied with.

“The Master, WILLIAM HUNTER, made the following statement: – ON Sunday 24th November, strong winds and cloudy; wind S.S.W. At 4pm wind S, weather clear; checked in the yards, and carried a press of sail, steering W. At 8o’clock Cape Las Hogue light in sight on the port bow, clearly visible from the deck, a very heavy head sea running, and the ship not making great speed in consequence. At midnight Cape Las Hogue light still visible from the deck, bearing about S or abeam. Weather still tolerably clear, but hauling to the westward. In consequence, reduced sail to lower topsails, reefed spanker, and reefed foresail. The ship being snug I lay down in the locker to get a rest with all my clothes on, leaving orders to be called at once if wanted. By 1am the wind had veered to W.S.W., the ship heading N.W. and N.N.W., going very little ahead. At about 430, the wind had again veered to S.S.W., the ship heading W and W.N.W., but going very little through the water, the sea being very heavy. Observed barometer 29.50, Portland lights bearing to the westward of north. At about 7am, Portland lights bearing north, distant about 14 or 15 miles by estimation, the barometer falling now to 29.30, on consulting with the First Mate I decided to bear up for Portland Roads. At 8 the weather got hazy, and the land was not visible. When watch was called, kept all hands on deck, squared the yards and bore away about N.N.E. to sight, if possible, the Shambles light vessel. After running about two and half hours, and thinking I was nearing the Shambles, the weather got very thick, with blinding rain, and not seeing the light vessel, I concluded I had passed it. Hauled up to N.N.W. hoping to sight the Isle of Portland, the ship being then under very easy sail, I knew land must be very close before I could see it. At about 1pm sighted land ahead, supposing it to be the Island of Portland, about Church Hope, as per chart, then bore away N.E. to try to pick up the Breakwater and round the east end of it, the weather being then very thick, with blinding rain. As I continued on that course I found the land still breaking through the thick weather right ahead and on the lee bow, at the same time the wind varying a little westerly. Fearing I had got to the leeward and on the Dorset coast I immediately wore round and hauled to the wind on the starboard tack and made sail to reefed upper topsails, reefed courses, spanker, jib, and main topmast staysail, but with great difficulty, as it was blowing a perfect gale with squalls and rain. The jib and main topmast staysail could not stand such awful pressure, and both of them burst, and were hauled down and secured. The ship appeared to be getting off a little further from the beach, and I was in high hopes of getting out of the bay, as the wind was now about W.S.W., the ship heading S by E , good full. At about 4pm I discovered a point of land right ahead, breaking through the thick weather. The ship being then too close to the shore to wear, and the sea running too heavy to stay, I concluded the ship would go on shore, and made preparation for anchoring, giving the Second Mate and Carpenter orders to have axes ready to cut away the mast if necessary. The Second mate was kept at the lead during most of the time the ship was coming along the shore, reporting from time to time “No bottom at 15 fathoms”. Lights were seen on the shore as it became dark after I had sent up rockets and burnt blue lights. The shore lights were evidently from some people on shore who were looking pout for us. The Second mate reported 15 fathoms, then 13 and 10 fathoms shortly afterwards. On finding this water, order both anchors to be let go, which was done and tried to check the ship’s head on to the sea, with 40 or 50 fathoms of cable out. Secured several of the sails before anchoring. The ship never swung to her anchors, but drifted on the beach broadside on, the sea breaking over the masthead. Could discern a great number of people on the beach, evidently with the intention of rendering assistance, they having lights burning close to the water’s edge. Shortly after striking, the First Mate, in attempting to get on shore with a line, was dashed against the side and drowned. We succeeded in getting a line from the shore, and apparatus apparently by line the mate was tying to land with. The rocket apparatus was also fired on board amid ships, and two means of communication made. At least five of the women and several men had gone on shore at the after communication, when a delay took place owing to the people being afraid to get into the basket. A man standing close to me begged me to get his children saved, he having two in his arms. I begged several women to take one, but could get no one to do so. The father himself could not try it. One women indignantly answered me “No, indeed, I will save no one’s child”. Seeing the delay and the valuable time losing I jumped into the basket and took the youngest of the two children with me, and in less than two minutes was safely landed. The child was taken out of my arms, and I requested to be allowed to go back to the ship as I intended, but was not allowed by those who hauled me on shore. After I left the people seemed to have more courage, and came more quickly from the wreck. The ship now broke up fast. The before mentioned man with the two children trusted another man with his remaining child but it was lost out of his arms and drowned. Two men were struck by falling spars and knocked overboard, and an old lady of 72 years of age, who had not left her bed since leaving London, could not be got out, she refusing to come when requested by the Steward and the Second Mate. The first woman who left the ship, Mrs IRONS, took hold of a rope attached to the ship, and the basket being hauled on shore she was dragged out and drowned. The last man to leave was a German, a very heavy man; when being hauled on shore the rope broke, and he was lost, making in all six passengers and the First Mate. Great praise is due to those in charge of the apparatus and to the men for saving so many lives in such a short time under the circumstances.”

Mr HUNTER writes to us as follows:

“My attention had been called to a letter in your paper of Monday, written by Captain W H PHIPPS R.N, respecting myself (incorrectly named MARTIN). I beg, through your columns, to thank him for the interest he has taken in my behalf by making public the information he so accidentally obtained. So many false reports have appeared in various papers, that if I had attempted to refute them all I must have neglected important business in connection with the wrecked property to do so. I have therefore determined to remain quite, trusting to be able, at the proper time and in the proper place, to give a satisfactory account of my conduct in every respect, and clear my character from the cruel aspersions made upon it. I will content myself how by confirming Captain Phipps’ statement that both anchors were let go before the ship came on shore: and in every other respect, except that I was not the third to leave the vessel, as implied therein”.

The Times: 7 December, 1872 – Continuation of Information.

“The official inquiry instituted by the Board of Trade into the circumstances attending the loss of the Royal Adelaide was resumed yesterday at the Guildhall Weymouth, before Captain WILSON and Mr STRONG; the former of Lloyd’s Salvage Association, and the latter of the Board of Trade. Arthur MAYO, Pilot of Chesil, said that if he had been onboard the Royal Adelaide about 4 o’clock on the afternoon of the day of the catastrophe – when he saw her in the bay – as Pilot, he could not have got her out; he thought there was no question about that. He did not think it was blowing too hard to carry sail to work her out of the bay. William WATTY, Chief Officer of the Portland Coastguard, said he worked the Portland “Breaches bouy”, but when the mizzen mast fell he was obliged to cut the line. About eight men, chiefly sailors, were saved by its use. The Wyke apparatus was also brought into requisition, and he and his men assisted in working it after the other had been disabled. The passengers crowded at the poop of the vessel, and hesitated to get into the apparatus, although they were signalled to do so from the shore. About 3000 persons were assembled on the beach, and he saw 14 or 15 apparently dead drunk. This witness, as also the others, bore testimony that the utmost possible was done for the saving of life and property, the Military and the police being indefatigable in the preservation of order. They were of opinion that it would have taken a much larger body of men than those on duty to draw a line for the protection of the property. There had been some unaccountable delay in informing the Receiver of Wrecks of the catastrophe, and this could not be cleared up. It was definitely laid down, according to the Board of Trade instructions, that the receiver of Wrecks was the responsible party to have command on such occasions, and to superintend the general proceedings. There appeared to have prevailed a considerable amount of misunderstanding on this point, for several of the witnesses had failed to report themselves to the Receiver of Wrecks. In the afternoon Captain WILSON and Mr STRONG, accompanied by Mr R.N. HOWARD. of Weymouth, proceeded to the scene of the wreck for the purpose of inspecting it. The inquiry was adjourned until today.”

The Times: 9 December 1872 – New Information.

“The official inquiry into the circumstances attending the wreck of this ship was resumed on Saturday, before Captain WILSON, an Inspector of the Board of Trade, when some new information was obtained.”

The Times: 16 December, 1872 – The Portland Wreckers.

“A special Sessions was held at the Shire hall Dorchester, on Saturday, to hear charges of being in illegal possession of cargo belonging to the Royal Adelaide, and refusing to deliver the same to the receiver of Wrecks. There were 18 summonses. Mr GILES SYMONDS, Town Clerk of Dorchester, prosecuted on behalf of the Board of Trade; Mr WESTON defended several of the accused persons, each of whom was liable to a fine of £100. By the testimony of the police it was shown that on the night of the wreck a large quantity of the cargo was carried away, including spirits. The first case disposed of was that of HENRY BOND, a private in the 77th Regiment, who had taken five bottles of spirits, for which offence the Officers of his Regiment had already sentenced him to 28 days imprisonment; the Bench now ordered him to pay 5s and costs. THOMAS COMBEN, Coal merchant, of Portland, had taken a cash box, which a Policeman found concealed under his Macintosh. His defence was that he was taking the box to the Lieutenant of the Coastguard, according to a custom observed in olden time. The box contained a gold ring, which was claimed by a lady from the ship. Defendant was fined £10 and costs. ALEXANDER COX was fined £40 and costs for taking pocket handkerchiefs. WILLIAM ELIOT, who had taken a tin, was discharged on payment of costs. GEORGE STONE alias THOMAS COSTES of Southwell was found possessed of twill lining, and as he gave a false name to the police he was fined £5 and costs. JAMES COLLINS of Easton Portland for taking two bottles of spirits, which he said he found on a pathway, was fined 40s and costs. SYLVESTER NORMAN who took one bottle of spirits was find 40s and costs, as was also WILLIAM SCHOLLAR for a similar offence. JAMES COLLINS DRYER took a case of oils and other articles, and the penalty was 40s and costs. WILLIAM PALMER found with 12 shirts on his back was fined £5 and costs. JOHN STONE of Weymouth for taking pocket handkerchiefs was adjudged to pay 40s and costs. JAMES COMBEN was ordered to pay costs. CHRISTOPHER DYMOND was fined 40s and costs. EDWARD PAULL an old offender was found with two bags of corks and the penalty was £5.and costs. Defendants were allowed time for the payment of the fines. Mr SYMONDS said the prosecutions were taken up from no vindictive spirit but in order to show the Portland people that such plunder as that committed on the wreck of the Royal Adelaide could not be allowed.”

The Times: 25 December 1872 – Official Inquiry.

“Yesterday an official inquiry, directed by the Board of Trade, and which had occupied the sittings of two previous days, was concluded at the Greenwich Police Court, before Mr PATTESON, the magistrate, and Captains HARRIS and HIGHT, Nautical assessors, into the circumstances attending the total wreck of the Royal Adelaide, and loss of seven lives, while on a voyage from London to Sydney, in command of Captain WILLIAM HUNTER, on the Chesil Beach, Portland on the 25th ult. Mr HAMMEL conducted the inquiry, and in a lengthened written statement put in by the Captain he attributed the wreck to blinding squalls obscuring the land and preventing him ascertaining his exact position until he found himself “embayed” and that the ship was then driven on shore by the violence of the gale and the heavy seas then running. The particulars of the wreck have already been reported. It will be recollected that the vessel was an iron ship, with iron masts, steel yards, and wire rigged, and was of 1385 tons registered. She carried a crew of 30 and 60 passengers, of whom the first mate and six passengers lost their lives. The following is a copy of the judgment of the Court:

“In reviewing the circumstances attending the loss of the Royal Adelaide the Court must notice the great want of caution exercised by the Master in attempting to run into Portland Harbour without having made the Shambles Light Vessel. From the courses steered it seems a miracle that the vessel was not lost on that dangerous shoal. At 7am, a bearing of the Portland light was obtained, N. by half W, at 8am the ship was steered NNE towards the roadstead. At that time the weather was so thick that the Shambles Light Vessel could not be seen; nevertheless the Master though uncertain of his position, altered the course to NNW, fortunately cleared both the Shambles and the Bill of Portland, and took the ship into West Bay. The Court is of opinion that the Master was not justified under these circumstances in thus attempting to run into Portland. This ship was neither crippled nor in distress, and being doubtful of his position he had the alternative of hauling his ship to the southward, and awaiting clearer weather. Again, when he found himself in a difficulty, had he had recourse to his deep sea lead, instead of the hand lead, he would have found, by a reference to his chart, that he was to the westward of the Bill of Portland instead of to the eastward of the Shambles as he supposed. Taking all these circumstances into consideration, the Court cannot attribute the loss of this ship to stress of weather but rather to the rash neglect of those precautions which as experienced Master Mariner is expected to exercise in case of difficulty and danger. The Court cannot therefore overlook the want of due care manifested by the Master whereby a valuable ship has been lost and several lives sacrificed. The judgment of the Court is that the Certificate of Competency of Mr WILLIAM HUNTER be suspended for the term of 12 calendar months from this date. The Court think it right to observe that they have not been directed to inquire into any of the circumstances which occurred subsequent to the stranding of the ship, an official investigation having already been made at Weymouth, and a report sent in to the Board of Trade”.

The proceedings then terminated.

Times: December 10, 1872 – Adelaide Subscribers

Captain R. HAMILTON R.N. of Her Majesty’s Ship ACHILLES writing to us under date Portland 7 December, asks us to publish the following list of subscribers to his appeal on behalf of the sufferers by the wreck of with the Royal Adelaide. He acknowledges with thanks the deep sympathy expressed for the suffers. Any omission he had made in answering inquiries and offers of other assistance, or any mistakes in so numerous list, he will do his utmost to rectify, if pointed out to him.

| Hammond (Lloyds) | £2.2s |

| R B Sheriden | £10 |

| J Titley | £1 |

| Colonel Alleyne | £25 |

| S Arnold | £5 |

| A.B. | £5 |

| H.C.M. | 5s |

| Major Littledale | £20 |

| W R Smee | £2.2s |

| Captain Tryon RN | £5 |

| W Moore | £3 |

| J Hunt | £5 |

| W Barber | £10 |

| M.C.W. | £3.3s |

| C.T. | £1 |

| Ann Cooper | 10s |

| M Williams | £1.1s |

| F.M. | 2s |

| R A Leggett | 10s |

| W S Brown R.E. | £5 |

| C.E. | 5s |

| Colonal Ogle | £3 |

| C.F.E. | 10s |

| Captain Gillett | £5 |

| E A Thrupp | 10s |

| Captain E R King | £1 |

| Admiral Talbot | £1 |

| Colonel Smith | £1.1s |

| M.M. | 5s |

| W Robertson | £2 |

| Mrs Eliott | £2.10s |

| Captain Crofton | £2 |

| Captain A Boyle | £5.5s |

| Hon Mrs Denman | £1.1s |

| Russell Earp | £12 |

| Mrs Tindall | £2 |

| Captain Davis 29th Regiment | £5 |

| Colonel Grant | £5 |

| Lady A Harvey | £1 |

| Mrs John Sheppard | £1 |

| Hon. Mrs Way | £5 |

| Hon Miss Stanley | £1 |

| Hon Louisa Stanley | £1 |

| Mrs H B Williams | £1 |

| Lieutenant and Mrs CD Broughton | £2 |

| Commander and Mrs J A Fisher | £2 |

| Commander Hare and Officers of HMS BOSCAWEN |

£6.16s |

| HMS ACHILLES | £6.17s |

| J S Grice | £2 |

| General H R Simesden | £3 |

| R G Coke | 10s |

| P | £1.1s |

| E Wootman | £1.1s |

| J M G | £5 |

| J Naylor | £5 |

| W G Rideout | £3.3s |

| M Stuart | £5 |

| Hon Mrs G Denman | £2 |

| General Darling | £2 |

| Mrs C Wilson | £2 |

| M B S | £2.2s |

| Admiral Crozier | £1 |

| Rev. Margison | £1 |

| G S Dunlop | 5s |

| Admiral Randolph | £5 |

| LA and HB | £1 |

| J H Toone | £1 |

| J W Lea | £5 |

| Jno Baring | £5 |

| Stamps | 2s |

| E Crispen | £1 |

| H N (Stamps) | 5s |

| S Worrall | £2.2s |

| S Steward | £5 |

| L H D | £3 |

| W R Scott | £3.3s |

| J H L Cambridge | £3 |

| G MacDonald | £1 |

| M B Walter MP | £5 |

| J C H | 10s |

| A L (Notes) | £10 |

| E W A | £5 |

| Lord A Churchill | £3.3s |

| S W Jennings | £1.1s |

| Mrs Hollingworth | £5 |

| John Noble | £5 |

| Henry Flaville | £1 |

| Captain W Boys | £1 |

| M Leslie | £1.1s |

| W L Gibbons | £1.1s |

| Octavius Wigram | £5 |

| T H Allan | £1 |

| S M P | £2 |

| H T | £3.3s |

| J A Young | £1 |

| F Richards | £5 |

| F Drew | £1 |

| G F Wilson | £5 |

| D C | £2 |

| Captain Burton | £1 |

| Rev. John Lynes | 10s |

| Sir George Jenkinson | £2.2s |

| W G Birch | 10s |

| Raymond Barken | £2 |

| Susette H | 2s.6p |

| D P | £3 |

| Mrs and Miss Winton | £1.10s |

| Colonel Levett | £1 |

| A Lady | £1 |

| John Stone | £5 |

| G F H | 5s |

| G E Howmen | £5 |

| Jane Phipps | £1 |

| F B Rodenham | £2 |

| H B Leggett Blackburn | £5 |

| Captain Thrupp RN | £5 |

| J O | £2 |

| Harry Coryton | £5 |

| T Baker | 5s |

| Miss R E Gripper | 13s.6p |

| O Hunter | £1 |

| Collected by W Yates | £2.7s.6p |

| Captain N B Smith RN | £2 |

| L C K | £2 |

| J C | 1s.9p |

| Colonel Ibbetson | £1 |

| X Y Z | £10 |

| Collected by H W Rideout | £20.15s.6p |

| Note endorsed WJ King | £5 |

| Mrs Gregory | £5 |

| Heathfield Smith | £5 |

| Anonymous or who do not wish to be named publicly | £22 |

| H A Meyrick | £50 |

| G T | 5s |

| Captain May RN | £1 |

| Captain Isacke | £2 |

| Mrs Evans | £5 |

| Mrs Walter Evans | £2 |

| J H | £1 |

| J H Barnett | £5 |

| J Maxwell | £1 |

| W R Lushington | £6 |

| Captain W B Philmore | £5 |

| Cosunopolite | £5 |

| Louisa Chesney | £2 |

| Archdeacon Huxtable | £2 |

| Rev. Robert Picton | 5s |

| Captain Maude | £2.2s |

| Mrs Birchall | £3.3s |

| A E | 2s |

| F W Tilly | £1 |

| H J Lloyd | £1 |

| Dr J Forbes | £1.1s |

| G Burrall | £2.2s |

| Mrs Browne | £1 |

| A Couch | £1 |

| A Bankes | £2 |

| E Mathey | £1.1s |

| T H Baker | £2 |

| G D | £2.10s |

| T Whittaker | £3.3s |

| Carry Schiff | £1.1s |

| E Robinson and Sons | £2.2s |

| R S (Stamps) | 10s |

| Sir W Ferguson | £10.10s |

| R | 10s |

| R S | 1s.6p |

| R D | £1.1s |

| W Clifton | £1 |

| Admiral R F Stopford | £2.2s. |

| D A Rougemont | £10 |

| Rev.H Hamilton | £2 |

| W E Beckett | £2.2s |

| A Jones | £1 |

| Parbury and Co | £2.2s |

| Colonel Sawyer | £5 |

| Thankoffering | £3 |

| F A Hamilton | £5.5s |

| St Leonards | £10 |

| E Manuel | £2 |

| R R | 10s |

| Captain Cockeran | 10s |

| E V Williams | 10s |

| Ellen R | 2s.6p |

| Admiral Thompson | £1 |

| Rev. A Orr | £2 |

| W Barlee | £5 |

| F F | 3s10p |

| Lieutenant General Staunton | £5 |

| Stamps | 2s.6p |

| C Sartoria | £10 |

| R B Marshall | £1 |

| W Brook | £1.1s |

| General Boileau | £1 |

| W W B | £5 |

| J W Hopkins | £5 |

| B D | £5 |

| J B | £4 |

| J W Previte | £1.1s |

| Mrs Howard Blythe | £1 |

| A B C | £3.5s |

|

THE END |

THE END |

Day of Loss: 25

Month of Loss: 11

Year of Loss: 1872

Longitude: 50 34.65

Latitude: 02 28.50

Approximate Depth: 12