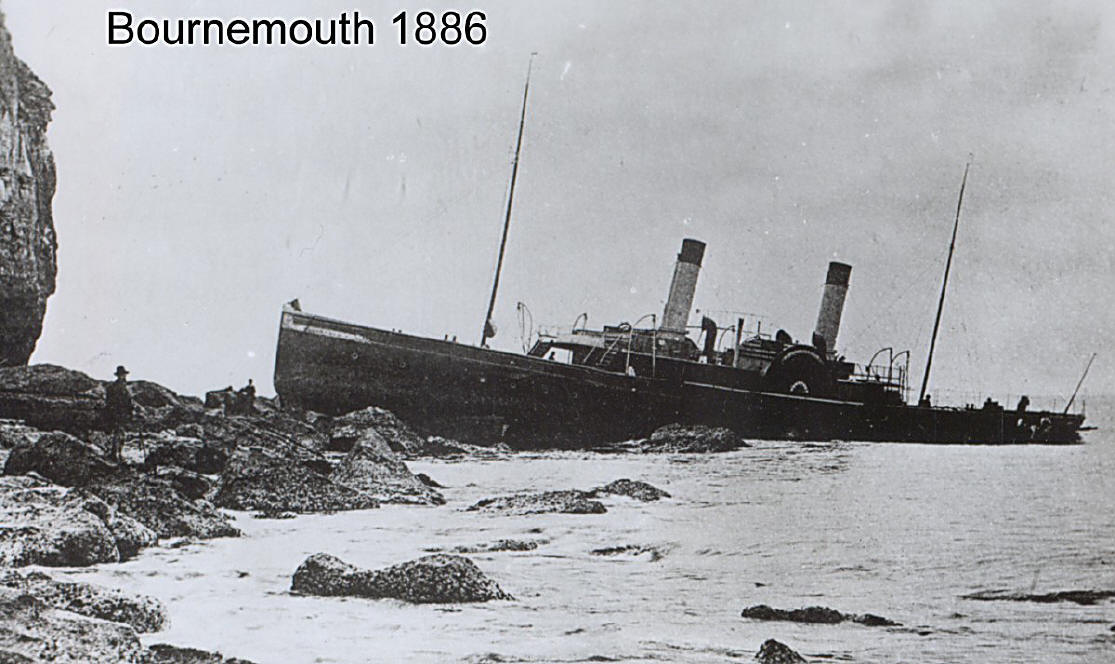

Paddle Steamer – Detail in Dive Dorset: 120 p100: GPS; 50 31.00N; 02 27.58W. (Southern Times: 03/09/1886) & (LARN) – West side of Pulpit Rock. Note: Name-board and dinner plates in Portland Museum. Report in DCC: 02/09/1886. (LePard: p83). Portland Museum Wreck No. 7. See Times Reports

Report transcribed from DCC by K. V. Saunders;

“Total Wreck of the Steamer BOURNEMOUTH – The receipt of a telegram on Friday evening intimating that a passenger steamer had run ashore under the higher lighthouse at Portland during a dense fog created an amount of excitement which, happily, is of rare occurrence at Weymouth. On the morning of the day named the VICTORIA steamer, Captain Cosens, left Weymouth for Dartmouth, the EMPRESS, Captain Bowring, and the BOURNEMOUTH, Captain Perrin, started from Bournemouth for Torquay, so that there were strong grounds for apprehension it was one of these vessels on which the misfortune had fallen. Under these circumstances, people flocked on the pier in order to obtain more definite information, and the utmost anxiety and suspense prevailed; in fact, it was not until the receipt of another telegram announcing that neither of the Weymouth steamers was the sufferer that the anxiety respecting the residents and visitors of the town in some measure subsided, but when the news was wired to Bournemouth that it was the steamer of that name which had gone on the rocks, the fears as to the fate of the passengers and crew were intense, and they were only alleviated some time after when the information reached the town that no lives were lost. It appears on Friday morning the EMPRESS, of Weymouth, and the BOURNEMOUTH, of Bournemouth, left the latter place for Torquay on a day’s excursion, the latter having about 200 passengers on board. Soon after leaving, on the return journey, both vessels ran into a dense fog, but all went well with the BOURNEMOUTH until land was suddenly discovered, and no sooner was it sighted, than the steamer ran with terrific force on some rocks, on which she became completely shelved, under the higher lighthouse on the west side of Portland, so violent being the shock that the steamers fire compartment was completely stove in. A scene of the greatest excitement ensued, but, fortunately, the sea was remarkably calm, and after the first shock preparations were made for saving the passengers. Signals for assistance were made, and these, happily, the men in charge of the lighthouse observed. Hastening to the spot and observing the perilous condition of both the passengers and the steamer, they telegraphed to Cosens and Co., of Weymouth, to despatch a tug, the only other intimation being that a passenger steamer was ashore. The tug QUEEN was immediately sent, although in the dense fog which still prevailed great risk was incurred in despatching her to such a rock-bound shore, but in spite of all obstacles and difficulties the tug was enabled to reach the scene of the wreck, though not in time to render assistance. In the meantime Mr. J. S. Fowler, the manager of the company, proceeded to Portland by land to conduct in person, with the assistance of Lloyd’s agent, the necessary arrangements for rescuing the passengers and crew of the ill fated steamer, and opening up telegraphic communication with the several towns from which the excursionists on board had come; for this purpose the post-offices were kept open until after midnight. Up to the time of the arrival of Mr. Fowler at Portland the name of the stranded steamer was not definitely known, but there was still an apprehension it must be one of the boats belonging to the Weymouth Company or to Bournemouth. As soon as Mr. Fowler reached Portland the boats on the beach were launched and sent forward to take off the passengers, another section going from the southern side of the island, and these with the other arrangements made afforded ample accommodation to safely and quickly land all who were on board. In case these means had proved to be insufficient the QUEEN steamer was expected on the spot, and it was hoped almost up to the last moment Cosens and Co’s steamer VICTORIA, from Dartmouth, passing some 40 minutes later, would be attracted to the spot by the signals of. distress, so that all the passengers of the BOURNEMOUTH might be transferred to one or the other of these boats. The fog, however, was so dense that the signals were not observed by any one aboard the VICTORIA and she reached Weymouth even before the QUEEN, carefully groping about in the fog, arrived on the scene of the wreck by which time the whole of the passengers and crew had been safely removed from the stranded steamer. The landing, which took place at Chesil Cove, was promptly carried out with the assistance of the chief officer and men of the coastguard service, large fires being made as signals where it was best for the boats to land, and also to give better facilities to help land the passengers. It may be mentioned the rocket apparatus was used most successfully and had it arrived earlier the whole of the passengers could have been brought ashore by that means. As it was four were brought ashore in the cradle.”

A Southwell Maid’s Diary By: Elizabeth W. Otter. Published: July, 1930.

The Wreck Of The S.S. “Bournemouth.”(Near Portland Bill, August 27th. 1886.) This fine pleasure boat one beautiful morn, Now the “Bournemouth” was a fast going ship, For the fog was dense but they, I suppose, And you may conceive the tremendous shock, And many grew frantic for loud was their cry, But in the meantime We’ll sound the alarm. Now the sound of distress was heard thro’ the Isle,

|

So the coast guards all without further ado With the life apparatus for saving the crew, And lights to burn on the gloomy cliff Set out for the wreck and were there in a jiff. And hundreds of people soon followed their track, To render what help they could at the wreck. Some ran for the boats, that was nearest at hand, And pulled for their lives, when once they were manned.Filling their boats till they would not hold more, They took them as fast as they could to the shore. Returning again and again, but I say There were men on the cliff as eager as they To save lives that were nigh without hope, And over the cliff some went with the rope; For they were so brave, courageous, and true, But felt so determined to rescue a few. But when the sad news got down to the Cove, But the beautiful “Bournemouth” had parted in two, And now I will give you the names of a few, And here I’ll mention another brave two, And Mr. John Peck hundreds to command, Robert Otter, Slobbs, Portland, Dorset.

|

Times: September 18, 1886 – Wreck Commissioners Court.

Captain Ronaldson and Captain Pattison were the assessors.

This was an inquiry into the stranding of the paddle steamship Bournemouth, 684 tons, under the higher lighthouse, Portland, in fog on August 27th last.

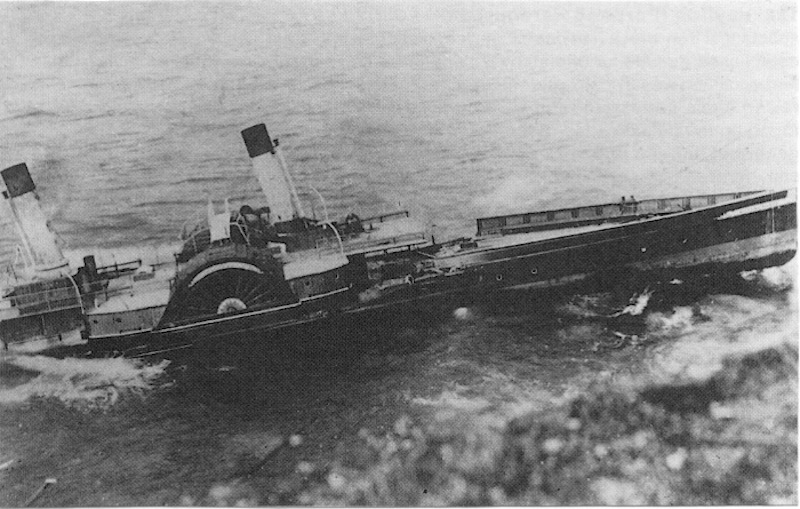

Mr W. A. Hunter opened the case on behalf of the Board of Trade. He stated that the Bournemouth was built in 1884, and belonged to the Bournemouth, Swanage and Poole Steam Packet Company. She was engaged in the passenger traffic between Plymouth, Dartmouth, Weymouth, and the Isle of Wight. She was surveyed on July 8thlast and found to be in good condition. She carried three lifeboats and a dingy capable of carrying 45 persons altogether. On July 1st the master certified that the compasses were in all respects satisfactory. On august 27th the vessel proceeded from Torquay for Bournemouth at 10 minutes to 4.00pm in the afternoon, with a crew of 14 hands and 180 passengers, the weather being fine and clear. She steamed about 15 knots an hour, her course being East by South half South from Torquay. A lookout was kept by three seamen, and at 6.50 the captain was about to stop the vessel with a view to sounding when the lookout shouted “rocks ahead”, and before the engines could be reversed she struck. The boats were lowered, and, with the assistance of the coastguard, the passengers were all got safely off. The crew left at 9 o’clock, and at about 11 o’clock she broke up. It was rumoured that the Bournemouth had been racing another vessel – The Empress – which left Torquay a quarter of an hour before, but he believed that the captain would state that that was not so.

The first witness called was William Perrin, certified master of the Bournemouth, who said that on coming up on deck at 5.30 there was a thick fog and they could not see more than 100 yards. The course was East by South half South leaving Hope’s Nose, the speed being about 15 and a half knots on the top of the tide. He kept the ship running on coming on deck from tea at the same speed and on the same course. The ship steered from the bridge. He was on the bridge on the port side and the boatswain on the starboard side, while two seamen were in the bows looking out. A 6 o’clock he reduced the speed to from 8 to 10 knots, and altered the course from East to South East. He did not take any soundings before the ship struck at 6.50, when he expected to be a mile or so to southward of the Bill of Portland. When the man on the lookout reported land ahead, he immediately gave the order “full speed astern”, and the engines were immediately reversed, but before that could have any effect the vessel struck. He immediately sent off three lifeboats with 32 passengers, and did everything he could to attract the attention of those on shore. Five and six boats which came from the shore were filled with passengers and sent ashore. The coastguard did not come until about 10. Only three passengers were sent off by rocket apparatus, it being about a quarter past 10 when the last passenger left the ship. Witness and the crew left the ship at half past 11. As the tide ebbed away, the rocks being nearly under her amidships section, she parted near the forward water-tight bulkhead. The vessel was insured for £7,000, but her value was from £10,000 to £12,000. There was only one standard compass onboard, which was last adjusted at the end of April this year. The deviation was only about one degree on the South-East course. The Steamer Empress left Torquay about an hour before he did, but he was not racing with her. He considered the stranding was due to the error of his compass.

James Henry Trodd, boatswain of the Bournemouth, who said that he did not hold any certificate, attributed the stranding to the in-set of the tide. He did not know whether there was anything wrong with the compasses. He thought due allowance was made for the action of the tide.

John Barber, who was steering the vessel at the time of the stranding, and William Boyd, the Engineer, having given evidence.

Mr Hunter said that concluded the evidence he had to offer, and the questions by the board were then handed in.

Mr Trevanion, addressing the court on behalf of the Captain, who had been a Master and Mate for 22 years without a casualty, urged that he had taken a proper course, that he kept a careful lookout, and that he did all that was possible for the safety of the passengers after the vessel had struck.

Mr Hunter having replied:-

The Chief Commissioner, in giving judgment, said that in the opinion of the Court the cause of the stranding was that the vessel was kept on a course too far to the Northward. One of the questions put by the board of trade was whether a safe and proper course was set and steered after leaving Torquay, and whether due and proper allowance was made for the tide and currents. It was clear from the evidence that the course which the captain steered was not a safe and proper course. For half an hour after he became aware of the fog he had continued on his original course and kept the Bournemouth going at full speed. The court considered that the vessel had been navigated in a most improper and un-seamanlike way.

It was not denied that the whole blame for the casualty rested with the Master, and the Court entirely concurred in the opinion of the Board of Trade that his certificate should be dealt with. They were told that he had been in the employ of the Isle of Wight Steam Packet Company for 22 years, and for the last three years in the employ of the owners of the Bournemouth. So long a service as that would not justify them in passing over so gross a case as this. If there had been only a little more sea and a little wind not a soul onboard the vessel would have survived. Under all the circumstances of the case, the assessors were clearly of the opinion that this was one of the worst cases they had had recently, and they thought, not with-standing Captain Perrin’s long service, his certificate must be suspended for 12 months.

On the application of Mr Trevanion, a mates certificate was allowed in the meantime.

Day of Loss: 27

Month of Loss: 8

Year of Loss: 1886

Longitude: 50 31.00

Latitude: 02 27.58

Approximate Depth: