HMS FISGARD II. Naval Training Ship [68M] – Dive Dorset: 116 p98 & Clarke: GPS; 50 28.23N; 02 29.44W. (Details also in LARN) 21 drowned. Originally the iron clad INVINCIBLE, then EREBUS (1904) and then FISGARD II (1906). Ref. DCC: 24/09/1914.

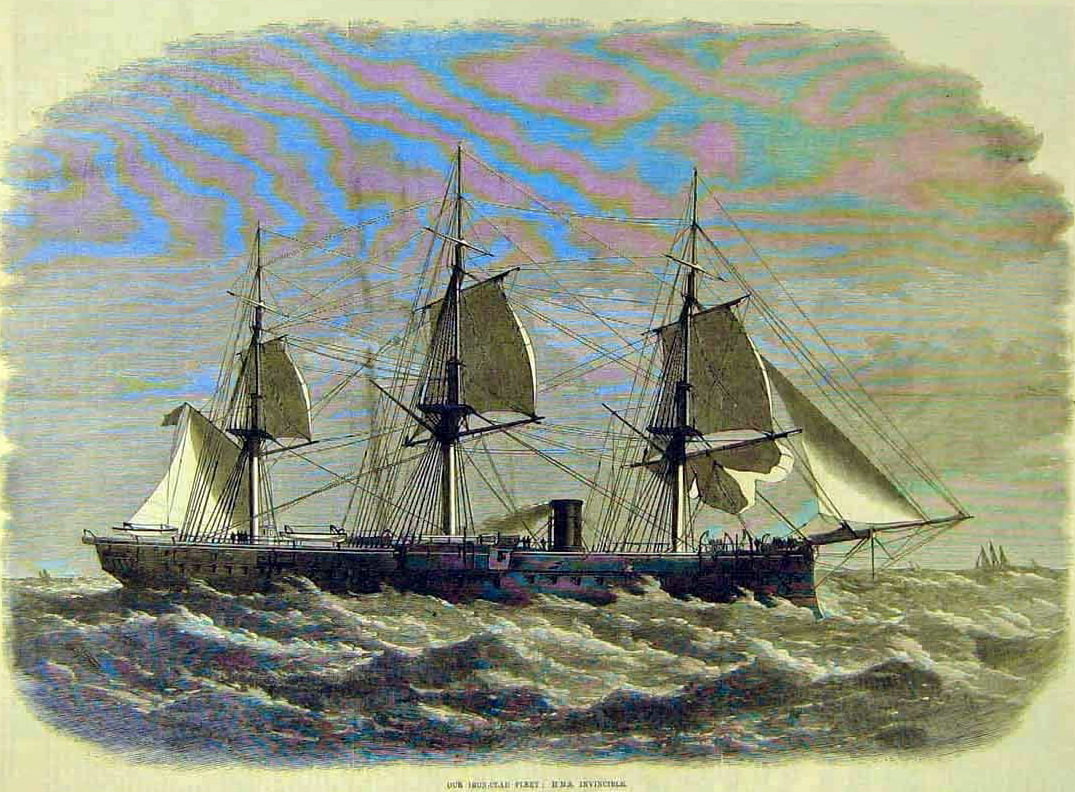

Print – Illustrated London News

Name: HMS Invincible

Builder: Napier shipyards

Laid down: 28 June 1867

Launched: 29 May 1869

Commissioned: 1 October 1870

Renamed: HMS Erebus in 1904 Fisgard II in 1906

Reclassified: Depot ship in 1901

Training ship in 1906

Fate: Sank, 17 September 1914

HMS Invincible was a Royal Navy Audacious-class ironclad battleship. She was built at the Napier shipyard and completed in 1870. Completed just 10 years after HMS Warrior, she still carried sails as well as a steam engine.

Class & type: Audacious-class ironclad battleship

Displacement: 6,106 long tons (6,204 t)

Length: 280 ft (85 m)

Beam: 54 ft (16 m)

Draught: 22 ft 7 in (6.88 m)

Installed power: 4,021 ihp (2,998 kW)

Propulsion: 1 × coal-fired reciprocating steam engine 6 × boilers

Speed:

Steam: 13.5 kn (15.5 mph; 25.0 km/h)

Sail: 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h)

Complement: 450

Armament: 10 × RML 9 in (230 mm) guns 4 × 64 pdr (29 kg) guns

Armour: Belt: 8 in (20 cm) (amidships); 6 in (15 cm) (ends)

Central battery: 6–8 in (15–20 cm)

Notes: Armour is backed by 10 in (25 cm) of teak.

The Audacious class was armed with ten 9 in (230 mm) muzzle-loading guns, supported by four 6 in (0.15 m) muzzle loaders. These were located in a broadside pattern over a 59 ft (18 m) two-deck battery amidships—this was the area of the ship least affected by its motion, and made for a very stable gun platform.

The Audacious class was armed with ten 9 in (230 mm) muzzle-loading guns, supported by four 6 in (0.15 m) muzzle loaders. These were located in a broadside pattern over a 59 ft (18 m) two-deck battery amidships—this was the area of the ship least affected by its motion, and made for a very stable gun platform.

For the first year of her career, she was a guard ship at Hull, before being replaced by her sister HMS Audacious. She was then transferred to the Mediterranean, where she served until 1886. She was sent to Cadiz in 1873 to prevent ships seized by republicans during the civil war in Spain from leaving harbour. She rejoined the Mediterranean Fleet in 1878 under the command of Captain Lindsay Brine, but her poor state of seamanship attracted the ire of the commander-in-chief, Geoffrey Hornby. In early 1879 Invincible blundered badly, putting two ships at hazard, and Brine was court-martialled. Though acquitted, Brine was relieved by Captain Edmund Fremantle. She was Admiral Seymour’s temporary flagship at the 1882 bombardment of Alexandria because his normal one, HMS Alexandra, drew too much to enter the inner harbour. She provided men for the naval brigade that was subsequently landed and she also provided men for Charles Beresford’s naval brigade in the Sudan campaign of 1885.

She made a trip to China in 1886 to carry out a new crew for Audacious before becoming the guard ship at Southampton until 1893. Her engines were removed in 1901 when she became a depot ship at Sheerness for a destroyer flotilla. She was renamed HMS Erebus in 1904, a name that she bore until 1906, when she was converted into a training ship at Portsmouth for engineering artificers and was renamed Fisgard II (HMS Audacious had been renamed Fisgard in 1904).

On 17 September 1914, she sank during a storm off Portland Bill with the loss of 21 of her crew of 64. She was being towed from Portsmouth to Scapa Flow where she was to act as a receiving ship for seamen newly mobilised for World War I. She now lies upside down with the bottom of the hull about 164 ft (50 m) below sea level.

DCC: 24/09/1914; Transcript by K. V. Saunders.

SINKING OFF THE BILL – An Old Battleship’s Doom Twenty-one Lives Lost – Great excitement reigned in the Island on Thursday afternoon, when it became known that from the cliffs and the beach a large steamer could be seen in tow of two tugs and with a liner standing by endeavouring to make her way to Portland, before serious harm befell her. The news ran round Tophill like wildfire that a large ship had sent out signals for immediate assistance, and soon some hundreds of people from every point of vantage had eyes and glasses fixed upon a grey vessel with one funnel and with a terrible list. They saw a large “liner” on the windward side trying to break the seas, and, strange, but more impressive, they also saw the helpless vessel drawing nearer and nearer to her doom, until at about 4.15 p.m., when she was just off the tail end of the Race, they saw her reel under a heavy sea, turn turtle and plunge beneath the waves.

No one ashore, except possibly the coastguard at the Bill, knew what the vessel was, and rumours innumerable flew about. But, whatever their opinions on the identity of the vessel, all agreed that her final plunge into the boiling waters was an awe-inspiring sight, while those with the better glasses could see that from her decks leapt many men, some of whom were picked up by the tugs, while others were saved by the “liner’s” boats. That all were not saved was the unanimous opinion, and, as events have now transpired, they were right, for 20 men whom the nation could ill spare went to their doom.

It was not until some time later that the identity of the lost vessel was made known. She was the FISGARD II, a naval training ship for boy artificers, which was on her way round to Cromarty to be used there in effecting minor repairs for the men-of-war, and she had something like half a million pounds worth of machinery aboard to enable her to carry out those duties. Her crew consisted of 64 men, some being naval or naval reserves and many others being dockyard hands and of these, up to a late hour at night, only 44 had been reported safe. The FISGARD II, which was formerly the EREBUS, stationed at Portland some 9 or 10 years ago as depot ship, until relieved by the IMPERIEUSE, was in tow of the tugs DANUBE and SOUTHAMPTON, and it was these which saved the majority of the men.

In the early afternoon she was reported by wireless to be in great danger, and assistance was sent out, but too late.

Late at night, after dark, the melancholy procession of tugs and “liner” steamed along by the breakwater with flags at half-mast, and then in came the saved. The tug DANUBE accounted for 19 men, the SOUTHAMPTON, and the “liner” for 25 between them. Most of the survivors landed in the pens, and were ordered to make their way immediately to the naval canteen, where a hot meal and dry clothing awaited them. The men were in pitiable plight as they walked up from the yard. Some had no boots, many were wet, for the fires of the tugs were not enough to dry all the clothing.

They told brief but expressive tales of the sufferings they had undergone, and spoke in terms of high praise of the gallant efforts made by the tugs and the “liner” to save life. According to their story; gathered in disjointed fragments by a Southern Times representative, the ship was going round to Cromarty as has already been mentioned. She was “light”, and had tons of machinery on her upper deck, and when she ran into the rough weather in the Channel she received such punishment that much of the heavy machinery broke loose and rolled over to the side, thus giving the ship such a list that further progress was practically impossible, and the tugs were compelled to try to make for Portland. “Her decks were all aslant like the roof of a house” said one of the saved, “we could scarcely stand on them, and we knew that if the towlines parted nothing could save us. Most of us looked out something to keep us afloat if the worst came, but when it did come it was so sudden that it caught many of us unawares. I found myself in the water near a buoy, and although I am told I was only in the water about five minutes it seemed like five weeks to me, for what with the howling of the wind and the shouts of our fellows, I seemed half distracted. One of our men held up another for a time; but I don’t know if they were both saved. A cruiser came racing up, but I don’t think she saved anybody, although they told us aboard that she had found a body.” All this was gasped out in disjointed sentences as the men made for shelter and food.

The following is a list of the men saved by the DANUBE:- Ship’s steward F. Smith, petty officer G. A. Mann, J. Morgan, and K. Broderick (R.N.R.), and the dockyardmen – A. Young, J. Banbury, A. Blake, F. Arnold, W. Jones, G. Lyall, W. Quinton, S. Hammond, Johnson Albert, A. Shaw, E. Peters, A. Johnson, A. Norkett, W. Smith, and R. Jordan.

They were all enthusiastically praising the treatment accorded them by Captain Jewis, of the DANUBE, who dried them as well as he could and gave them something to keep out the cold, looking after them as though they were his own children.

One of the men rescued, named Mc Ritchie, died after being brought ashore.

The fact that there was a vessel in distress was quickly signalled to Weymouth, and the S.S. MELCOMBE REGIS, one of Messrs Cosens and Co’s powerful tugs, was immediately despatched. She left the harbour at 3 o’clock; but the vessel went down just as she arrived on the scene.

Captain Read told a representative of the Southern Times that they were quite close to the vessel when she went down. She suddenly turned right over and went down. Her stern was out of the water for a moment, and then she disappeared from sight. She was being towed by two tugs, the SOUTHAMPTON and the DANUBE II. A big transport came up and put out 2 boats. He saw a lot of men running along the deck of the vessel as she turned over, and subsequently saw them in the water. Both the boats of the transport picked up men until they were full, but as they got alongside of the transport one of them was thrown against the side by a heavy sea and smashed. The men in her were rescued by means of ropes thrown over the side. An English cruiser also came on the scene, but he did not think she picked up any men. There was a lot of wreckage about, and all the ships on the scene cruised about among it for a considerable time in the hope of picking up survivors. The FISGARD seemed to have steam in her, as he saw it coming out of her as she want down.

We learn that the machinery did not break loose until just as the vessel was sinking. The cause of her going down was the amount of water shipped in through the hose pipes. The crew were trying all day Thursday, shifting what little ballast she had, to try and right her.

References:

Dictionary of Disasters at Sea During the Age of Steam, 1824-1962. by C. A. Hocking. Vol. 1 p243.

Ships of the Royal Navy (SRN) Vol. 1 p284.

Dorset Shipwrecks p55.

Additional Note:

The seventh “INVINCIBLE” was a twin-screw 14-gun broadside ironclad, launched at Glasgow in 1869. She was of 6010 tons, 4830 horse-power, and 14 knots speed. Her length, beam, and draught were 280ft., 54ft., and 23ft. In 1873 the “Invincible,” commanded by Captain John Clark Soady, was one of a small squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir Hastings Yelverton, which proceeded to the Spanish coast and established a blockade of the Spanish Mediterranean littoral. She assisted in the operations against the Spanish Intransigentes and prevented the insurgent ships from bombarding various coastal towns. In 1879 the “Invincible,” commanded by Captain Lindesay Brine, was one of a squadron of seven ships which occupied the island of Cyprus under Vice-Admiral Lord John Hay with his flag in “Minotaur.” In 1882 the “Invincible,” took part in the Egyptian War. In July 1882 the “Invincible,” commanded by Captain Robert More Molyneux, lay at Alexandria in a fleet of 14 ships commanded by Admiral Sir Beauchamp Seymour with his flag in “Alexandra.” The Egyptians having failed to surrender their forts, the Admiral transferred his flag to the lighter draught ship “Invincible,” and on July 11th at 7a.m. the “Alexandra” fired the first shot in bombardment of Alexandria. The “Invincible,” with two other ships, was stationed inside the harbour, and she fought at anchor with a spring on her cable. All ships were cleared for action, topgallant masts being struck and bowsprits rigged in. By 7.10 a.m. all ships were engaged, and all the forts that could bring their guns to bear replied with vigour. By 5 p.m. all guns ashore had been silenced and the fleet ceased bombarding at 5:30 p.m. The “Invincible” had several dents on her armour, and was penetrated more than once outside it. The British casualties were 5 killed and 28 wounded , to which the “Invincible” contributed 6 wounded, including Midshipman Walter Lumsden. The Egyptian loss has never been properly ascertained, but it is believed to have been about 150 killed and 400 wounded , out of the 200 men engaged in working the forts. On July 13th the “Invincible,” and other ships steamed into the harbour, and landed men who occupied and policed the town, Paymaster Stanton of this ship becoming the Head of the Commissariat. On August 5th the “Invincible” contributed to a Naval Brigade which left Alexandria in the armoured train which was commanded by Captain John Fisher, of the “Inflexible.” Commander Reginald F.H. Henderson, of the “Invincible,” accompanied the brigade. The marines were detrained about 800 yards from Mehallet Junction, and assisted by a 40-pounder Armstrong gun, quickly dislodged the enemy. During the evening the brigade was exposed to a galling fire, but the marines behaved with great gallantry, and bore the brunt of the attack. The casualties in this affair were 1 marine killed and 12 wounded, and 1 seaman killed and 4 wounded. The Naval Brigade were then recalled to their ships. In 1885 the “Invincible” contributed to a Naval Brigade which operated on the Nile, under Captain Lord Charles Beresford. It took part in the battles of Abu Klea, Metemmeh, and Wad-Habeshi, and the relief of Sir Charles Wilson. Captain Robert More Molyneux was rewarded with the C.B. for his services. In 1904 this ship’s name was changed to “Erebus.” At a later date her name was changed again to “Fisgard,” and she was merged into the establishment for the training of boy artificers in Portsmouth harbour. On September 16th, 1914, this ship foundered off Portland in a heavy gale. She was being towed at the time, and 21 men were drowned out of the 64 on board.

Day of Loss: 17

Month of Loss: 9

Year of Loss: 1914

Longitude: 50 28.23

Latitude: 02 29.44

Approximate Depth: 68

Aliases, aka: Invincible, Erebus