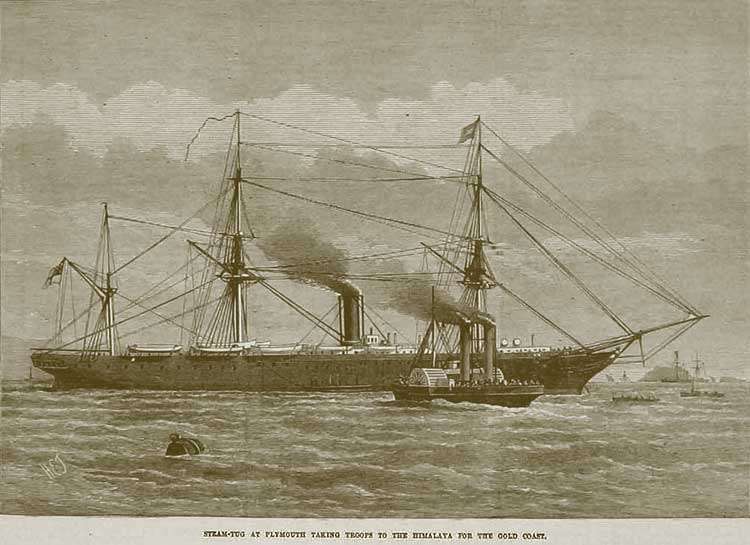

Steamer [11M] – (Excellent detail & photograph in Dive Dorset: 131 p106 to p107: GPS; 50 34.70N; 02 26.50W) (More detail in LARN, 1939). “HIMALAYA built 1855 by Mare & Co. (Blackwall) for P & O Company to carry 400 passengers. 372ft. 2in. overall 3,438 tons gross (largest merchant ship of the day). Plates of her bottom were 7/8″ thick tapering off to 13/16″ fore & aft. Originally designed with paddle machinery because the Admiralty preferred mail to be carried by paddlers. Owners changed to screw propulsion before delivery. Used as a troop ship during the Crimean War, later sold to the Government. Her end came in June 1940, when bombed by German Aircraft which sunk this stout old ship. She was then at Portland, serving as a coal hulk.” (LePard: pages 66 & 67) Also Merchant Ships in Profile by Duncan Haws, 1978. & Ships Monthly No. 11.

Himalaya (1940)

PRIDE OF THE P AND O

By STUART NICOL

In 1854 the HIMALAYA was the world’s largest ship. She served in the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the Ashanti War and the First World War, and she was still afloat in 1940 – until bombs sank her. The author pays tribute her to a tremendous ship with an extraordinary history.

The original HIMALAYA was the world’s largest ship according to the P and O Centenary History, almost its fastest and certainly the envy of every ship owner up and down the British Isles – every ship owner, that is, except the Royal Mail Steam packet Company, which claimed that its ATRATO was the world’s largest at 3467 gross tons (against the HIMALAYA’S 3438 gross tons).

It is not a point to quibble about: in many respects the ships were so similar that (apart from the ATRATO’S paddle wheels) they might have been originated from a common design, modified only for their differing trades. Each accommodated about 200 first class passengers, each possessed six watertight bulkheads (impressive in those days), each advertised a speed of 14 knots, and their maiden voyages from Southampton, early in 1854, were separated by just 56 days.

Compared with the GREAT BRITAIN, whose record tonnage they both surpassed, the HIMALAYA has long since passed into obscurity. It is one of those anomalies which cannot be explained, for the first HIMALAYA was a splendid ship with an extraordinary history.

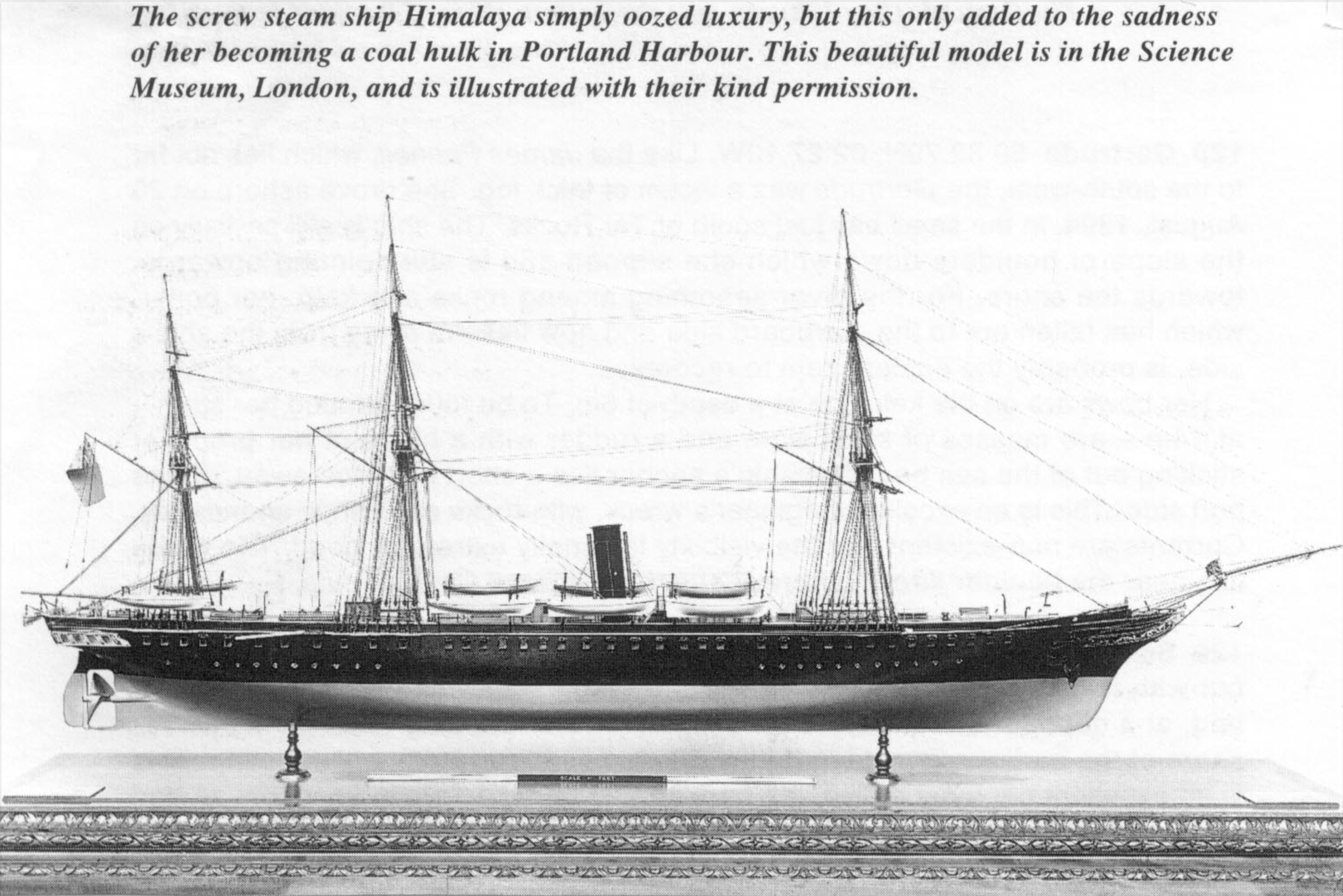

She was built on the Thames, at Blackwall, by C J MARE and Company in the plans of T WATERMAN, Jun and was laid down in November 1851, launched in May 1853 just ten years after the GREAT BRITAIN, and completed in January 1854. Her three masts were all square rigged, the main towering 150feet above the weather deck. There was little sheer to her hull, and the single funnel, slightly raked, stood in isolation, like a lone sailor on watch, above the open deck.

Her passenger accommodation was luxurious for the 1850s. She had a complement of 213 officers and men, and there was storage for 1200 tons of coal to fuel the trunk engines of 700 nominal horsepower built by JOHN PENN and Sons of Greenwich. With a length of 340 feet between perpendiculars, a breadth of 46.2 feet and a draught of 21.4 feet she had a displacement of 4690 tons.

In the 1850s the Suez Canal had not been dug and P and O still had to employ a link service on the Australian route. One ship sailed between England and Alexandria, and after making an overland crossing to Suez, the passengers boarded a second vessel to complete the voyage to India and Australia.

The HIMALAYA was scheduled to run between Southampton and Alexandria – presumably to show herself off in European waters. As a prestige ship she was a hugh success form the very first. On trials in Stokes Bay she reached 14 knots; when she steamed through the Mediterranean between Malta and Alexandria, her bows cut the water at 16 knots. Her Master Captain A KELLOCK, maintained that in favourable circumstances he could have squeezed out 18 knots.

On the outward and homeward legs of her maiden voyage she broke every record. Her success must have especially please the directors as they had persuaded the Admiralty to change from paddle to screw propulsion while she was actually being built. The Admiralty, of course, were the overlords of all British shipping lines blessed with mail contracts. Their dogged reluctance to accept such developments as screw propulsion and iron hulls was largely the reason why companies like P and O lagged somewhat in the technology race.

When the HINALAYA reached Southampton at the end of her triumphant first voyage, a writer in The Illustrated London News said: “ The success of this gigantic vessel is now established… Her measurements within and without, her palatial saloon and sleeping cabins, her promenade deck, in short, her multitudinous appliances, the power and speed of her engines, all have been told; and I shall only add that there seems now to be no question of the superiority of the screw, in vessels of large tonnage, over the paddles, as regards speed, economy of space and fuel”

If the owners were at all complacent after this praise their satisfaction was short lived. By the end of that record voyage they realised what a problem they had on their hands. However “prestigious”, a ship might be, she still had to make money, and in this the HIMALAYA was unlikely to be successful.

To maintain her high speed (in spite of the supposed economy of the screw method) she used a great deal of coal, and coal prices had just risen by 50%. For such a big ship her passenger capacity was not excessive, and with the large bunker requirements her cargo space was limited. In addition, the worsening trouble in the Crimea had brought about a reduction in trade, both freight and passenger.

Strangely enough the Crimean War turned out to be the salvation of the HIMALAYA. On only her second voyage she was chartered by the Government for trooping duties to the Black Sea. She was immensely popular with the soldiers who sailed in her, and later in 1854 the Government offered to buy her for £130,000, scarcely less than her original cost.

CRACK TRANSPORT

P and O agreed to the sale, doubtless relieved although the deal stipulated that they should maintain the vessel for a year. Her Chief Officer was asked to remain for the same period as no one else understood the complexities of her splendid engines. Suddenly her capacity increased from a spacious 200 to a crammed 1850. Even so, she was a great success, the crack ship of the transport fleet.

An extra deck was built from the forecastle to the funnel and was later extended right aft… There was a new colour scheme too – white hull with a Blue Riband and a buff funnel. First the mizzen and then the mainmast had their yards removed as greater reliance was placed on machinery.

After the Crimean War, the HIMALAYA spent some time repatriating the Army and she also took troops out to quell the Indian Mutiny in 1857

For the next 30 years or so she was busily employed relieving British garrisons abroad and naval ship on foreign stations, and taking part in the general ebb and flow of troop movements. She served in the Ashanti War of 1874.

Her early popularity was such that even when she was utterly outdated – placed among the “slow, cockroach ridden museum pieces “ as those troopers of the 1850s have been described – a respect for age, and a misty, cobwebbed dream of early graciousness, kept her free from the cold blooded swing of the axe.

O course, the axe had to fall eventually. The HIMALAYA survived until 1894, when the Government abolished the Royal Navy’s own Transport Fleet in favour of vessels chartered from the Merchant Navy. She was paid off and went into the reserve, the oldest active seagoing vessel on the Navy List.

As a hard working 40 year old she should have been ready for honourable retirement. Her early success, when she glinted like a diamond among the lesser gems, was long over. The slow grinding down of her brilliance in the tough world of war, that was over too. As for the years of quieter, plodding voyages, through Atlantic storms – all that long tale belonged to the past.

The last remnant of the splendour that once had been hers were hacked away at a shipyard on the Humber. As though to emphasise that the heart had been torn out of her, her proud name was removed and she was prosaically re-christened “ HM HULK C60” The Navy towed her to Devonport as a coaling hulk.

Queen Victoria’s long reign ended, but still the iron hull of the HIMALAYA served its purpose. In 1910 she took briefly to the sea again, rounding the coast to a new berth in the Medway. There she played her part, fuelling ships of the Harwich Naval Force during the First World War. In 1920 she was sold to a private coaling firm and was on the move again, still watertight, still useful, returning down channel to Portland.

The HIMALAYA lasted until June 1940 when 85 years after her keel wad been laid, a stick of Luftwaffe bombs dropped out of the sky and put paid to the ship that had been the pride of the P and O Fleet in 1854. (ks)

‘A Tale of Two Hulks’

THE ANATOMY OF A CLUB PROJECT

BY COLIN FOX

I put the mouthpiece of my Mistral between my lips, sucked, and swallowed half a cup of briny water that has been sloshing about in the bottom of the inflatable. I was already on the point of nausea from sitting cramped on the overloaded boat for a couple of hours in a heavy swell and this really was the last straw. With the upmost regret I turned and called on Bill!!! So ended my first attempt at diving.

A few hours later, in the relative calm of Portland Harbour, my diving career began. We were to dive on the wreck of an old coal hulk, known to all as the HIMALAYA, ex troopship in use during the Crimean War and sunk during a bombing raid in the last War. The wreck is arguably the best novice dive site on the south coast being well sheltered by the breakwater, easy to locate, reasonable depth (40 feet to the deck) and above all, actually looking like a ship, being perfectly upright with little sign of damage. Being a coal hulk there is practically nothing in the way of superstructure, and as the bulk heads have for the most part collapsed, it is easy and quite safe to swim from the chain locker past the heads through the three holds and into the stern where there remains but a skeleton of a deckhouse and single davit. All the goodies have long gone so there is no chance of the novice being discarded for something brighter.

The underwater viz that day was superb, and I still retain a deep memory of descending the anchor rope and seeing the wreck laid out before men in sweeping panorama. Colin Cook my dive leader, showed me around and although I took in little beyond the glass of my mask, the sense of excitement remained long afterwards.

I have dived that wreck many times since, and when I became Projects Officer of Oxford Branch two years ago, I decided to go ahead with a plan that had been germinating for some time. It was to measure and prepare a drawing of the wreck.

THE SURVEY

First thing was to draw on the collective memory of the Branch divers and obtain a sketch of the wreck – before we could measure anything we needed a picture, however inaccurate to work from. This proved surprisingly difficult to obtain. After hours of diving the wreck, the report of the divers could only be said to be diverse. In the end I decided that the first dive would be to try and obtain this elusive and inaccurate picture. The divers went down with instructions to remember a small part of the wreck with rough dimensions, the result was most gratifying – at last we had something to work on. During the weekend this survey took place, a group of us were chatting to some local people, and one of them mentioned seeing a sketch of the HIMALAYA in a boat yard at Ferrybridge. This sounded interesting, so taking Pete Shield, the Branch ace photographer, with us, we went for a look see.

The vessel depicted in the drawing was very different to the wreck we had dived on. It was quite possible that during hulking the silhouette had changed, but the HIMALAYA was powered by steam as well as sail and on our wreck there was no sign of any stern shaft – the rudder was direct onto the keel as in a sailing ship.

Back in Oxford, I went hunting through library and bookshop and came up with a paperback “Ships – a picture history” complied by Laurence DUNN, published by Piccolo. In this book there was a picture of the HIMALAYA together with a brief history.

THE HIMALAYA

“HIMALAYA (1853) The wonder ship of her time and by far the largest steamer afloat, the HIMALAYA was designed for the London – Alexandria section of the P and O Eastern mail service. She was converted from paddle to screw propulsion while building, the Admiralty having previously vetoed anything but paddles. She proved exceptionally fast, and on occasion under sail and steam she logged 16 ½ knots. With the Crimean War she was first charted and then bought to become a Naval Transport, and she continued as such until the eighties. Thereafter a coal hulk, she was bombed and sunk in Portland in 1941”

Date; – Owners P and O Steam navigation Co

Builders – C J Mare and Co, of Blackwall

Launched – May 1853

Maiden Voyage – January 1854

Tonnage (gross) – 3438 tons

Displacement – 4690 tons

Length – 340 ft

Breadth – 46.2 ft

Depth of hold – 34.9ft

Draught – 21.4ft

Speed – 14 knots

Passengers – 200 saloon

Engines – 1 set trunk type 2050l.h.p

Screws – one two bladed

A MYSTERY

Our survey, gave estimated dimensions as length 200ft, breadth 25ft – surely we could not have been so much out? But, if this wreck was not the HIMALAYA, what was it, and more important what had happened to the HIMALAYA which had quite certainly sunk somewhere in Portland Harbour.

Becoming more and more intrigued, I wrote to the Imperial War Museum for any information they might have – result, nothing known. I wrote to the Hydrographic Department at Taunton – their information was that the wreck we were surveying was the HIMALAYA.

In the mean time, a second survey had been conducted by ERIC ROBERTS (Diving Officer) and ERIC BARGENT, and this confirmed the dimensions as length 240ft and breadth 29ft, as well as adding many more details to the drawing we were preparing. The method used in this survey was interesting. Briefly, it incorporated the use of a reel of very cheap packaging twine which was stretched across areas to be measured, cut, and tagged. Back on dry land each piece was measured with an ordinary tape measure. The tags were labelled before diving commenced, and thus a great deal of information could be gathered quickly and relatively easily.

Pondering the next move, I was given inspiration at the BSAC Chairman’s Conference in 1974, “Get some good publicity for your Branch, Appoint a Press Officer”

Well, the HIMALAYA had sunk in 1940, so there must be quite a few people who had seen her go and were still living in Weymouth. I wrote to the editor of the Dorset Evening Echo, enclosing a sketch of the wreck we had been surveying, a copy of the wreck list from the Hydrographic Department and also a copy of a highly informative article in Ships Monthly (April 74) on the HIMALAYA by Stuart NICHOL. In my letter I managed to introduce the word ”mystery” three times, which I hoped would act as psychological bait.

The result was highly satisfactory – the paper not only printed a 7 inch paragraph, but gave it ½ inch headlines “Two Mysteries of the Harbour Wreck” and even printed the sketch I had sent them! The following week was one of the most fascinating I have ever spent. Every post brought at least two letters.

From Mr W A SYMONS – the ship you are diving on is not the HIMALAYA, she was bombed and sank on her moorings at lease ¾ mile from the breakwater. These are facts for I was on a tug at the time, and we tried to save them and put them ashore but no luck (The HAYTAIN), another coal hulk, was sunk at the same time).

In the middle 1830’s – about I would say 1936 – in a strong blow, a coal hulk went ashore there, we went to her assistance but she sunk on the tippings with her stump masts and Temperly gear (a form of rig for loading and unloading coal) just above the water, this gear was removed by a local firm BASSO and TURNER and the ship slid down the tipping and would I presume (be) very close to the stones at the bottom of the Breakwater. The name of this one could be COUNTESS OF ERNE ex-railway paddler.

From Mr G H CARTER: The HIMALAYA sank on the 5 June 1941 bombed by a Junkers 88 from 500ft at 21.20 hours( I would like to acknowledge the help Mr CARTER , who is preparing a history of Portland and who has subsequently given me much information on the area).

From Mrs D MONGER: My husband who was Trinity Pilot at the time she (The HIMALAYA ) sank, could tell you that she lay with her masts above the water all the war and was then blown up by the Admiralty salvage people after the war. He thinks the wreck you are interested in is either THE LINKS or THE COUNTESS OF ERNE – they both broke adrift before the war, one drifting through the North ship channel, one going ashore on the Breakwater about a cables length to the westward of A Pier Head. (THE LINKS was in fact the MINX, another coal hulk).

From Mr D W BRAY: I was working as a temporary signaller with the RN, I was 15 at the time and in the Scout movement. I was signalling from the top of the Nothe Fort when the old coal hulk was bombed and sunk. We saw the German planes flying over the oil tanks and saw the bombs dropping. At first we thought they were after the oil tanks. The bombs were delayed action and as far as I can remember there were 6 or 8 bombs, most going in the water.

Incidentally on the wireless next day “LORD HAW HAW” claimed that German aircraft had sunk the Aircraft carrier ARK ROYAL in Portland Harbour.

Condensing the information received, it seemed most likely that the wreck on the breakwater was the COUNTESS OF ERNE and that the HIMALAYA had been sunk somewhere in mid harbour, had lain with her masts above water throughout the war, and had finally been blown flat after the war.

Extract from “Railway and other Steamers” by C D DUCKWORTH and G E LANGMUIR: “PS COUNTESS OF ERNE built at Dublin in 1868 this steamer had the reputation of being the fastest in the L.N.W. Fleet. She was employed on the Dublin route till 1873 when she was transferred to the Greenore station. About 1890 she was reduced to a coal hulk and for many years lay in Portland Roads”

DATA;

Owners – CHESTER and HOLYHEAD RAILWAY CO

BUILDERS – WALPOLE WEBB AND CO DUBLIN

TYPE – IRON PADDLE STEAMER

ENGINE – BUILDERS – FAWCETT PRESTON AND CO

LENGTH – 241.4FT

BEAM – 29FT

DISPLACEMENT – 14.3FT

TONNAGE (GROSS) 830 TONS

NET Horse Power: 300

I wrote back to everyone who had contacted me, thanking them for their letters. To try and locate the position of the HIMALAYA I enclosed a Photostat copy of Portland Harbour and s.a.e. and asked if they would mark on the chart where they thought the ship had sunk. Also, I tried to encourage them to mark down any other wrecks they might know about. I was beginning to realise that I now had introduction to several interesting people. The result of this approach was not too successful. I got as many different positions as I had charts – only to be expected I suppose.

We did plan a search, however, in what seemed the most likely area. It was what I choose to call a Swastika pattern. Four pairs of divers set off along the cardinal points, each pair going 100 fin strokes turning right 90 degrees doing a further 100 fin strokes turning right, doing 50 fin strokes and finally one more right turn and 100 fin strokes. It does not cover the ground very efficiently but I reckoned good enough to find a wreck over 100 years long. In half an hour 8 divers can cover about 20,000 square yards. We found nothing.

Back to the writing desk, I penned a letter to the Queens Harbourmaster Portland Naval Base. The reply was discouraging: “I have made local enquiries regarding the wreck of the HIMALAYA. You are right in saying that the wreck on the inside of the breakwater is not the HIMALAYA, and I am grateful to you for ascertaining that it is probably THE COUNTESS OF ERNE. HIMALAYA was demolished by explosives at some time after the war. The pieces were cut up and landed at Castletown Pier for scrap.

Well having come this far, I was determined come hell or high water I was going to find some remains of the HIMALAYA, even if it was only a rivet, after all, she was once the largest ship in the world. If she had lain with her masts above water for any time, she must have been charted.

Letter to the Hydrographer: In exchange for information on THE COUNTESS OF ERNE, how about a copy of a chart of Portland for the period, say, end of 1941 to 1945?

I was overwhelmed by the generosity of the response. Free of charge I was sent copies of charts for 1934,1945,1946 , a large scale chart for 1945, and a new metric chart. Low and behold, there she was, clearly marked and on the 21834 chart, a coal hulk was marked over the same position.

Transposing the position on to the new chart was simple, as was finding some good transits. It gave a position about half a mile south of where we had planned our search.

On Monday 31st March 1875, after a bitterly cold Easter during which three quarters of our party had returned home, seven of us set out in the fibreglass boat owned jointly by Mick PHIPPS, Eric BARGENT and Max GOODY. Diving that day were Barry WINTERS, Max GOODEY, Pat MARNEY, Graham RACKEY, Tony RAVEN, Geoff HUGHES and myself. We sailed out along one transit until we closed the other. The echo sounder was switched on and immediately we picked up a scattered echo. Tony and Geoff were the first down. Two minutes later they were back up “There’s plates and wreckage everywhere”!

I dived with Graham. At 40ft we entered a cloud of stirred silt, headed north and after a few fin strokes found ourselves hovering over a plain of grey ooze from which protruded a tangle of unrecognisable metal. We took a closer look. It was immediately obvious that what we were looking at was the remains of an old ship that had been blown up. The plates were iron and not steel, riveted and not welded. There were badly distorted. We explored further. Odd lengths of pipe a lot of waterlogged wood – that struck a cord.

Letter from Mr W C COOK: In the days following the bombing, the wind was easterly and a considerable quantity of wreckage was washed ashore. This timber was teak, and I collected some of this from which later I was able to make various articles:

We came across many pulley blocks – part of the Temperley gear? Getting low on air we decided to bring a couple up – still bound together with tarred rope. The sheaves, when stripped apart, were found to be thick with coal dust.

We had only explored a relatively small amount of wreckage – how much more lay round about? After everyone else had dived, Graham and I decided to go for an anchor ride. Grabbing a fluke each, Max guided the boat over quite a large area. We were down to 30 atmospheres apiece before we came across any more extensive wreckage – no time for more than a brief look before it became imperative to surface. Max had taken some marks; we would return. (ks)

Day of Loss: 12

Month of Loss: 6

Year of Loss: 1940

Longitude: 50 34.70

Latitude: 02 26.50

Approximate Depth: 11